We’ve just worked through the CMA’s 637-page Final decision report (and a few appendices!) on the UK cloud infrastructure market. It’s packed with genuinely interesting data and analysis — the kind of numbers you rarely see in public (even if some of the juiciest bits are, inevitably, redacted).

This post pulls together a few of the findings we think matter most for public bodies and anyone building on the big clouds. It’s not about dunking on particular vendors; the CMA has already done the diagnosing. Our aim is simpler: highlight where incentives create lock-in and show how open standards + smart procurement keep your options open.

For more than a decade, the UK Government has championed openness, declaring in the 2012 Open Standards Principles that “government technology must remain open to everyone… [ensuring] our future technology choices will be affordable, secure, and innovative.”

For more than a decade, the UK Government has championed openness, declaring in the 2012 Open Standards Principles that “government technology must remain open to everyone… [ensuring] our future technology choices will be affordable, secure, and innovative.”

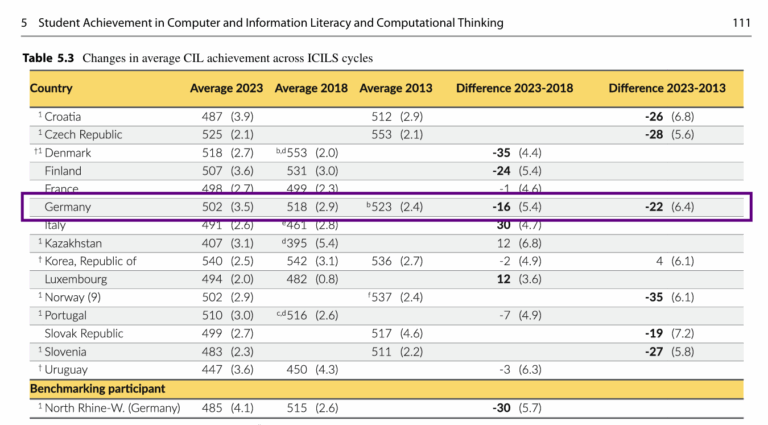

Yet, as the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) bluntly stated earlier this year as the very first point of their 637 page report into cloud infrastructure services, “competition is not working well.” They found that, “less than 1% of customers switch provider each year” (point 24) citing barriers such as “the presence and magnitude of egress fees required to transfer data between cloud providers” (point 26) and technical hurdles from “the differentiation of features and interfaces in cloud services, meaning that customers are inhibited from switching or multi-cloud as they cannot easily compare, substitute, or integrate services from different providers.” (point 27)

Meanwhile, the UK government’s budget for cloud services goes up every year. A recent The Register article highlighted projected spending on Microsoft services over the next five years to be £5 billion. That’s £5,000,000,000. In response to a parliamentary question about the total spend on digital services from Microsoft over the past year, Georgia Gould MP admitted she was unable to provide a complete figure since “individual departments and public bodies are responsible for their own procurement […] however the Crown Commercial Service [has spent] approximately £1.9 billion on Microsoft software licenses in the financial year 2024/2025.”

The numbers are sobering, and the CMA’s assessment damning. It’s enough to leave government officials, and indeed every UK tax payer, asking, “How did we get here?!”

How did we get here?

A Decade of Drift into Dependence

The seeds of the UK government’s dependency were sown in 2013, when the Cabinet Office introduced its “Cloud First” policy for central government. The idea was simple: by default, departments should evaluate public-cloud solutions before considering on-premise alternatives. In theory, this would promote agility, save money, and avoid the expensive, bespoke IT systems of the past. All good?

In practice, however, “Cloud First” became “Two Cloud Hyperscalers First”. With the largest platforms (Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Microsoft) offering attractive terms, bundled services, and rapid deployment. It was easy for departments to sign on, and hard to justify looking elsewhere. Over time, critical workloads, data, and infrastructure all became deeply embedded with these two providers.

In 2025, the results are stark. AWS and Microsoft together control up to 80% of the UK cloud market. Once locked in, high switching costs, proprietary architectures, and restrictive licensing have made moving away prohibitively difficult – exactly the kind of vendor dependence that the 2012 Open Standards Principles were meant to prevent.

The Licensing Trap

You might think vendor lock-in is all about proprietary technology, but it’s also baked into the fine print of contracts and licensing terms. In their report, the CMA singled out Microsoft’s licensing rules as a major structural barrier to competition in the UK cloud market.

Under their terms, products such as Microsoft Office, Windows Server, and SQL Server cost significantly more to run on rival cloud platforms than on Microsoft’s own Azure service (for example, the Azure website states that migrating SQL Server to Azure VMs rather than AWS EC2 instances is up to 23% cheaper.) Customers who want to transfer existing on-premise licences to the cloud (known as Bring Your Own License – BYOL)* find they can only do so cheaply if they choose Microsoft Azure – running the same workloads on AWS, Google Cloud, or another smaller provider trigger extra fees or requires buying entirely new licences. As the CMA put it, “Microsoft’s licensing practices are adversely impacting the competitiveness of AWS and Google […] which is reducing competition in cloud services markets.”

This makes switching away from Azure far less attractive, even when rival providers might offer better performance, price, or features. It also undermines “multi-cloud” strategies, where organisations spread workloads across multiple providers for resilience and flexibility. Instead, once a department deploys Microsoft workloads in Azure, the financial penalty for moving elsewhere can be so steep that sticking with Azure feels like the only viable option – a textbook case of vendor lock-in.

*A mini case study inside this case study further illustrates the problems: in February 2025, Microsoft announced it would retire its previously supported BYOL policy for third-party vulnerability scanners (like Qualys or Rapid7) narrowing choice even for customers who stay on Azure. Customers who once had the flexibility to integrate their own scanning tools now must switch to Microsoft’s proprietary solution. A microcosm of the broader trend – support for outside tools is initially offered, then withdrawn in favour of Microsoft’s own platform, reducing portability and choice.

The Egress Fee Barrier

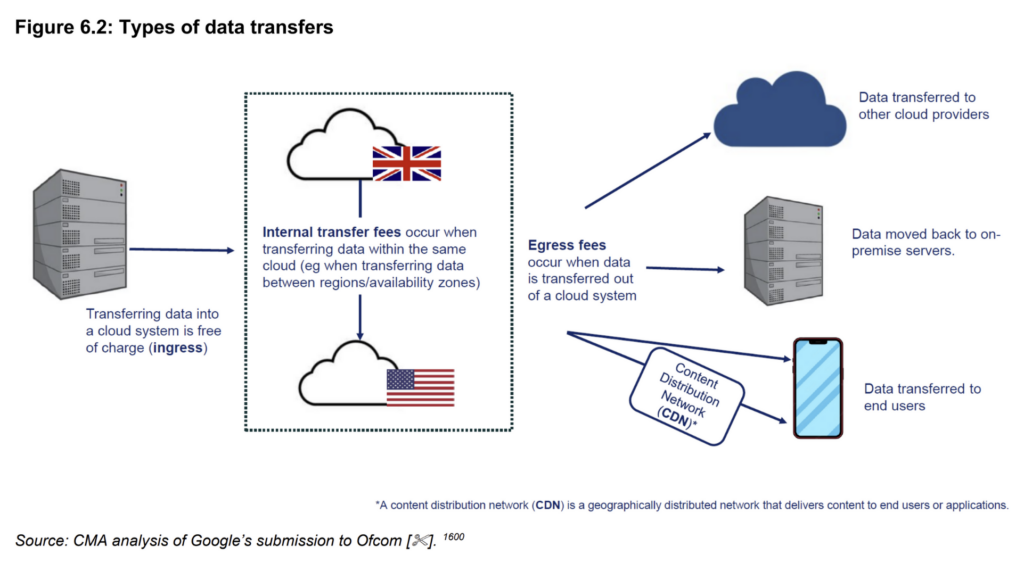

If Microsoft’s lock-in lever is licensing, AWS’s is data transfer pricing – better known as egress fees. These are the charges customers pay to move (their own) data to another provider or back on-premise.

If Microsoft’s lock-in lever is licensing, AWS’s is data transfer pricing – better known as egress fees. These are the charges customers pay to move (their own) data to another provider or back on-premise.

The CMA’s investigation found that the “presence and magnitude” of egress fees were “a key commercial barrier” to customers who would like to change service provider.

Defending themselves and referencing a 2017 IDC Report for the European Commission, AWS told the CMA that “the egress fees incurred by switching customers represented less than 5% of their annual spend […] but did not explicitly explain how they calculated the estimate” (6.401 (a)). Microsoft also referenced the same report (6.401 (c)) and Google provided the same “less than 5%” figure (6.401 (d)).

The CMA challenged these figures however, noting that “the analysis referenced by both Microsoft and AWS used an individual ‘mid-sized’ customer with a specific workload as the base for its analysis. No reference was made to this customer being representative of any wider customer group and there is no reason to believe this is the case. We also consider that the 2017 IDC analysis is likely outdated given how much the markets have evolved in the eight years since its publication. We therefore consider this analysis is unlikely to be indicative of the egress fees the average customer may expect to be charged when switching” (6.403 emphasis added).

Additionally, “We further note that both AWS’ and Google’s analyses are based on customers that have been identified as having switched. Basing such an analysis on customers that have switched will only capture those customers that considered egress fees low enough that they do not disincentivise switching and will tend to exclude any customers that found egress fees too high and were deterred from switching. We therefore consider that these analyses may underestimate the cost of switching, and therefore we place less weight on these results relative to our own analysis of switching costs ” (6.404 emphasis added).

So what did the CMA’s own analysis suggest? Some customers “would have had to pay egress fees of more than [15-30]% of their annual cloud spend in a year” (Appendix M, M.37).

Clearly, these fees benefits AWS (and other hyperscalers) at the expense of competitive pressure. As the CMA put it, “We have not found any customer benefits clearly resulting from the charging of egress fees” (6.590), and “our conclusion is that egress fees reduce the ability of and/or incentives for customers to switch to other cloud providers and/or run a multi-cloud architecture. They also reduce the incentives of providers to compete for the business of their competitors” (6.591).

The Regulatory Wake-Up Call

To address the imbalance, the CMA is recommending that Microsoft and AWS in particular be designated with Strategic Market Status (SMS) under the new Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act. This designation would allow the CMA to impose targeted interventions on specific practices that undermine competition and lead to vendor lock-in.

The question now is whether these measures can meaningfully unwind more than a decade of drift into dependence – or if, as history often shows, it’s easier to write new policies than to loosen old entanglements.

Lessons and a Call to Action

The UK Government’s own principles are clear: technology choices should remain open, affordable, secure, and innovative. Yet over the past decade, the combination of “Cloud First” procurement, hyperscalers’ questionable tactics, and limited enforcement of open standards has created exactly the opposite – an IT estate deeply dependent on two dominant suppliers.

The CMA’s questioning of the dominance and anti-competitive practices of Microsoft and AWS is an important step, but designations won’t guarantee change. It will take political will, rigorous enforcement, and procurement reform to make a difference.

For public bodies and the rest of the market, the lessons are straightforward:

- Don’t just write open standards into policy – enforce them in procurement.

- Avoid companies, architectures and contracts/licenses that are designed to make moving difficult or expensive.

You should use software because you want to, not because you’re locked in. Collabora Online (along with our many partners) exists to make this choice possible – an open-source, open-standards, fully-featured and collaborative office suite you can easily run in your own environment or choice of cloud provider (Azure, AWS, STRATO, OVH Cloud…), integrate with your own servers or Kubernetes/OpenStack, even a Raspberry Pi for labs and demos, choose from our existing integrations, and even migrate away from without penalty! Because true digital sovereignty comes from systems designed to give you control.

And if anyone from the UK Government is reading this, why not give our demo a try? We’d love to help you live up to your Open Standards commitment to keep “government technology open to everyone […] affordable, secure, and innovative.”